Designing for a 1,5-Meter World: Why the Designers' Toolkit Won't Save Us

Managing human behavior in the face of a global pandemic has become an urgent wicked problem.

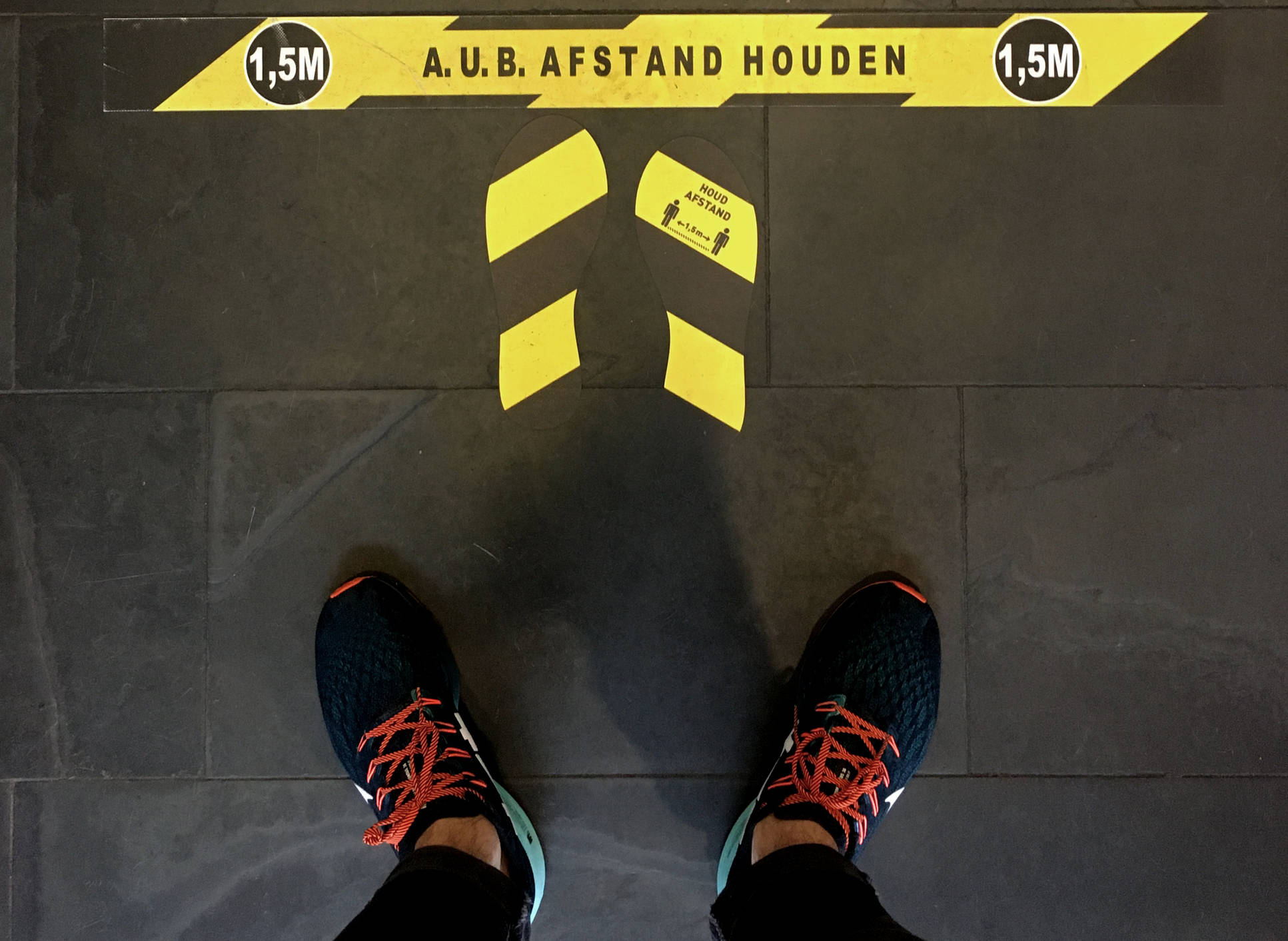

By now we’ve all observed the new signage and hygiene phenomena that began emerging in the first few weeks of quarantines and lockdowns that swept the globe.

Floor stickers, window signs, sanitizer stations, plexiglass shields, etc. have all quite suddenly permeated our everyday landscapes. From the grocery store to the train station, from municipal offices to the local gym (after it opened back up, of course), we’re now greeted with a barrage of instructions, warnings, and nudges that define our new “1.5-meter world.”

Designing for Adherence

This marks a powerful opportunity for design. Because as much as we’ve all observed the spread of pandemic signage and hygiene in public spaces, we’ve also all begun to observe its failure. From Amsterdam to Paris to Madrid, we Europeans increasingly seem to be ignoring the posted ephemera that prescribe life at 1.5-meters.

And yet, the coronavirus isn't canceled yet. Completely giving up on pandemic-safe behavior presents serious risks of renewed outbreaks. Indeed, we already see hotspots re-emerging in parts of France and Spain, to say nothing of the viral wildfire spreading across the US. But while many, if not most, people seem aware of this threat, why does our existing landscape of behavioral guidelines seem to be failing?

Given how many of the materials and protocols of the 1.5-meter world often feel improvisational or temporary, we designers might be tempted to see the problem as simply a matter of expertise. “If only this stuff was more professionally designed, it might be taken more seriously,” goes the argument. And of course, given half a chance, we designers can easily identify and address the many shortcomings of our social-distancing landscape. Weak iconography? Graphic design will do the trick! Poor legibility? Infodesign and infoviz has you covered! Garbled communication? UX copy can fix it right up! Inconsistent messaging and arbitrary rules? Consider some service design! Or maybe it’s just plain bad signage? In which case wayfinding will cure what ails you.

Solutionism is not the Solution

But I’m hesitant to seize upon fixes that look and feel like comfortable territory for designers to claim. For sure, wayfinding, graphic and information design, UX copy, etc. all suggest massive room for improving people’s commitments to corona-safe behavior, but they also feel solutionist.

Which is to say, I don’t think we’re likely to address the problem of social distancing and hygiene compliance by using the technical fixes easily at our disposal. While the critique of solutionism usually gets leveled at the digital industry’s “there’s an app for that!” mentality, infodesign, UX copy, and wayfinding are just as much at risk of being reductive technical fixes in our current situation.

I don’t think we’re likely to address the problem of social distancing and hygiene compliance by using the technical fixes easily at our disposal.

But, Nudging

Nudging has seen something of a renaissance during the pandemic (and here, and also here in Dutch). A design buzzword for almost a decade, nudging emerged out of the behavioral sciences as a tactic for guiding people’s conduct and decision-making everywhere from marketing to public policy.

And although some skeptics have suggested nudges are manipulative and undemocratic, gentle behavioral management can feel like all that stands between us and apocalypse on the one hand and authoritarian lockdowns on the other. Plus, nudging’s scientific pedigree gives it an air of credibility beyond mere technical fix.

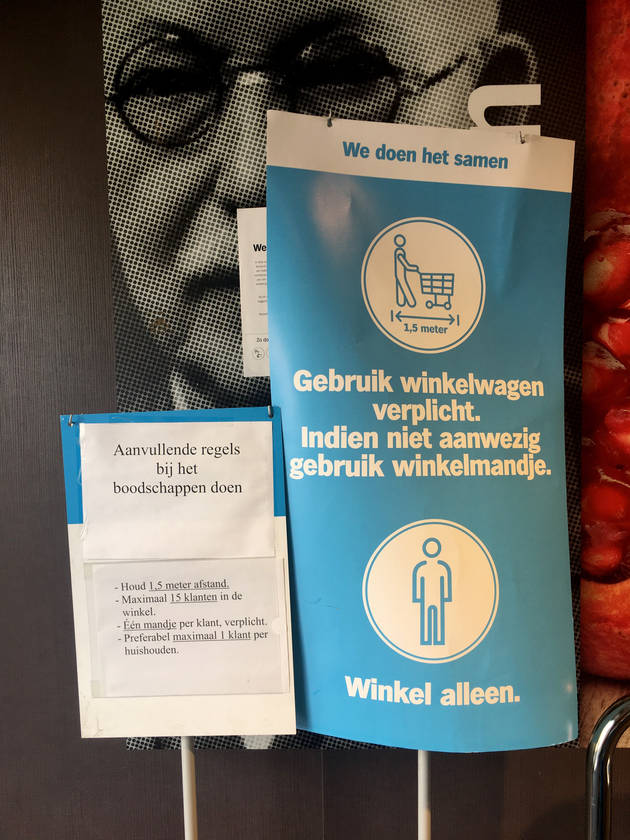

Signage in an another grocery store tells customers: "Shopping carts required. If none are available, use a basket."

Indeed, here in Amsterdam, I’ve observed social-distancing nudges that seemed quite successful, at least initially. Many stores use a limited number of shopping baskets to control how many people enter at any one time (no basket, no entry). Meanwhile, in March and April, a major grocery chain, also kept people 1.5m apart by requiring customers to use full-sized shopping carts. Train stations, meanwhile, have reconfigured automatic doors and disabled some ticket machines to manage the movement and clustering of people. Although these last two examples might count more as a shove than a nudge.

Nudging Nudged Out

Alas, even these seemingly elegant ways of managing people’s behavior are also becoming ineffective. Along with tuning out the signs, caution tape, floor stickers, and so on, people are increasingly skipping the sanitizer station, entering stores without a basket, crowding in queues, and even leaning around plexiglass shields to talk to shopkeepers and service workers.

Meanwhile, critiques of the pandemic nudge and its shortcomings are mounting, especially in countries like the UK and Sweden that have chosen softer approaches to the crisis over strict lockdowns. Meanwhile, the latest research in behavioral science suggests there are fundamental limits to nudging as a means of getting people to do what they don’t really want to do. Despite its academic origins, nudging is also turning out to be an overhyped, superficial technical fix.

Designing for Adherence: A Wicked Problem

So, what to do?

Well, for one, designers—particularly user experience designers—have behavioral science, psychology, and sociology in our ancestry. It’s time to lean into those roots and accept that people’s failures to follow coronavirus protocols run far deeper than poor communication design, weak icons, or insufficiently coercive nudges.

What our present crisis demands of designers is not just off-the-shelf technical solutions like copywriting, service design, and nudging, but a concerted design research effort to dig deep into complicated, squishy stuff like behavior, emotion, cognition, and risk.

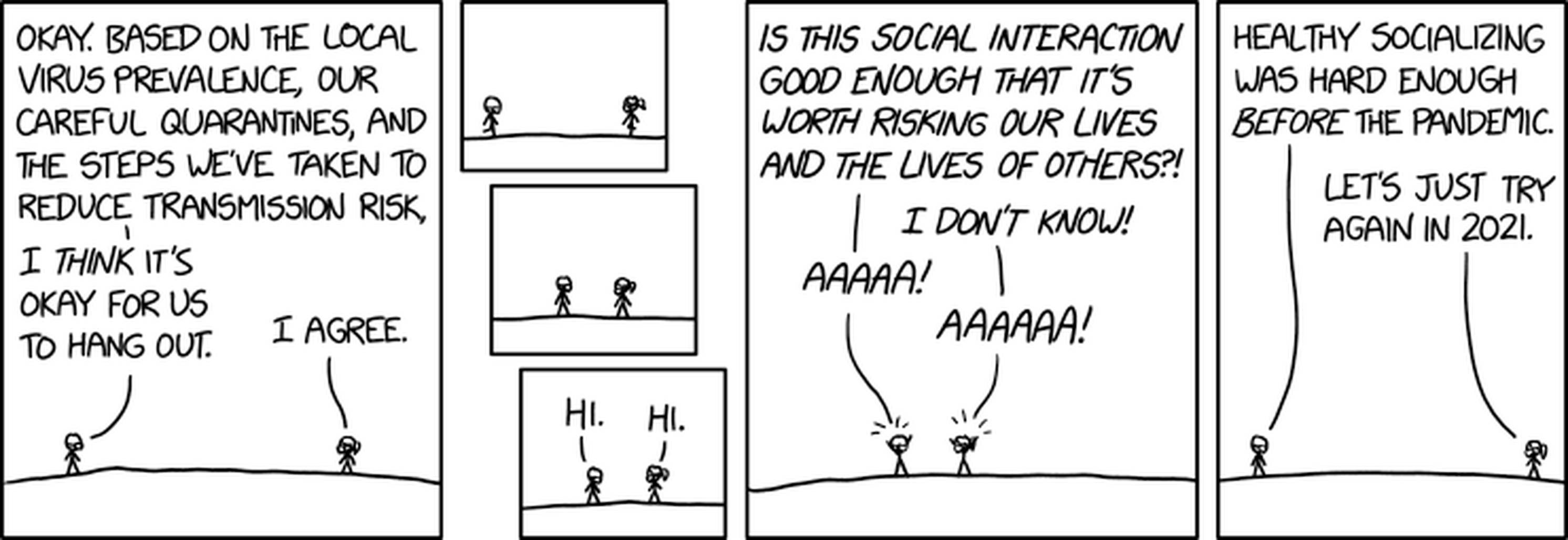

There’s a whole range of things at work in the pandemic that human beings are fundamentally bad at internalizing and negotiating: exponential growth, statistical probability, uncertainty, and risk all make it almost impossible for us to behave rationally in this situation.

Meanwhile, the deeply unsettling nature of an invisible threat and timescales that don’t match up too well with everyday life make adherence to our 1.5m world both cognitively and emotionally exhausting. Caution fatigue is very real, as is its more selfish companion, lockdown fatigue (“but I need that haircut!”).

This all puts us firmly in the territory of A wicked problem. And while you might cringe at the cliché, managing not only people’s behavior around COVID-19, but also all the economic and social consequences of that behavior, shares a lot in common with our struggles to address something as vast and complicated as climate change.

Much in the same way that the commonplace tools of design aren’t going to cut it with climate change, they’re also not going to cut it with ensuring people adhere to corona-safety protocols. What our present crisis demands of designers is not just off-the-shelf technical solutions like copywriting, service design, and nudging, but a concerted design research effort to dig deep into complicated, squishy stuff like behavior, emotion, cognition, and risk.

To be sure, it’d be much, much easier, far more marketable, and a hell of a lot more reassuring to throw ourselves into churning out new infographics, floor decals, services, apps, and behavioral hacks. But without investing serious time in the emotional and cognitive worlds of life in the time of corona, I imagine most of our design “solutions” will fail much, much sooner than later.

Thanks to Ruben van Bambost, Julia Brinkmann, Anna Offermans, Iris Richardson, and Patrick Sanwikarja for their contributions to this piece.