Hack the system!

This article previously appeared as an essay in the Dutch Designers Yearbook 2021 of the BNO.

About thirty years ago, we had clear ideals as designers: we wanted to design good, beautiful things. Functional, aesthetically pleasing and preferably a bit ground-breaking. Even back then, we were eager to make a difference. As a designer, you wanted to work for an agency, and hoped to do assignments for the Dienst Esthetische Vormgeving – the design department of the Dutch post, telephone and telegraph company. That gave you freedom and guaranteed your work would be seen. But in recent decades a clear shift has taken place.

To start, influenced by the digital revolution, we focused increasingly on the user. In the noughties, every designer’s favourite buzzword was ‘user-centred design’. And that’s rather embarrassing of course, because we could have come up with that much sooner. Now we have reached the next phase. Browsing through the recent design yearbooks and reflecting on Dutch Design Week, you can only conclude that we’re all throwing ourselves into solving societal problems. Serious topics like the climate, health and security are hip and happening. And rightly so – there’s a lot of work to be done. The optimism of responsible designers is lovely and heart-warming, but does it actually achieve anything? What are the results? Or in other words, are we on the right track with our righteous intentions?

Context

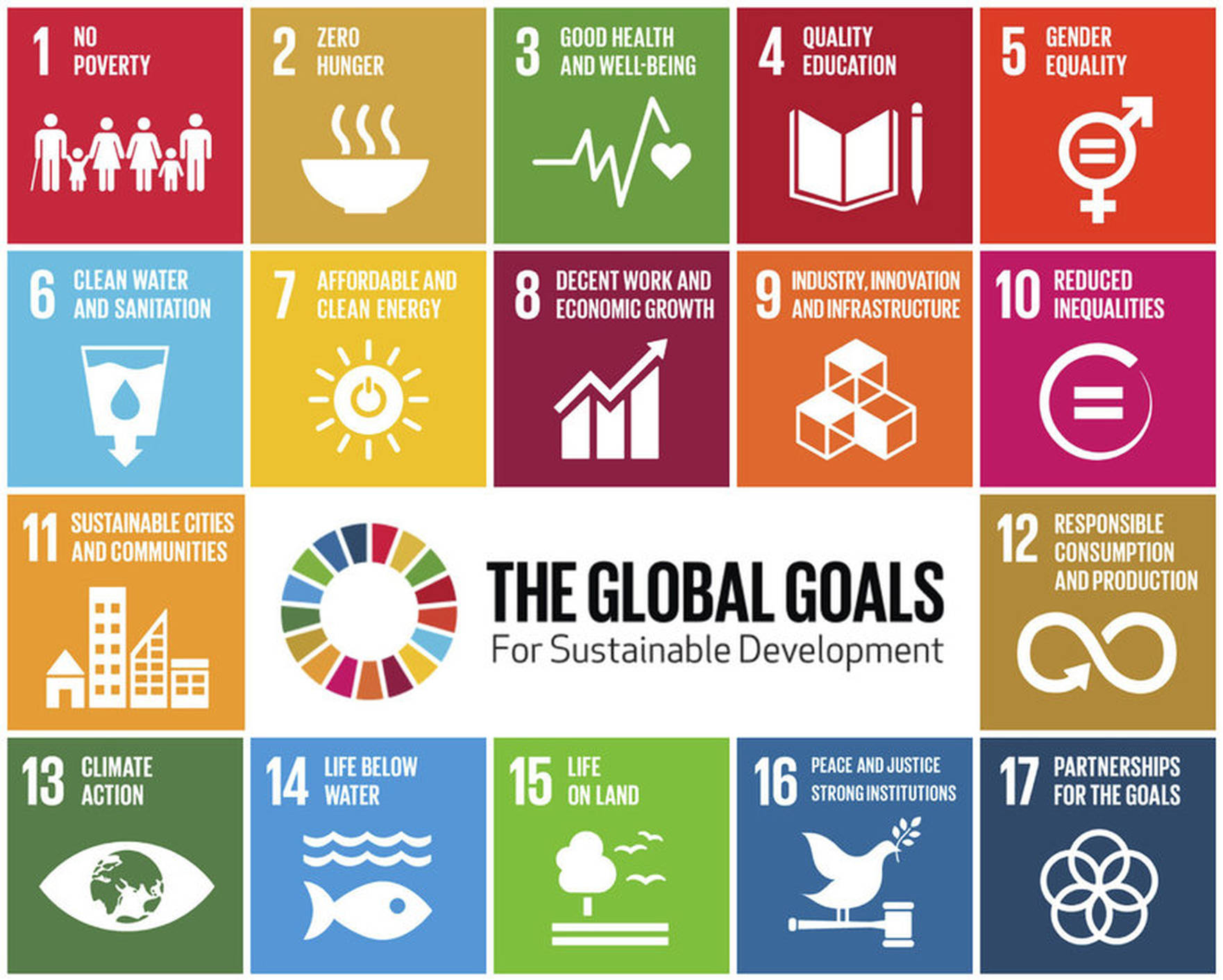

What we make and do definitely has an impact on the growing awareness of current and future problems. After all, ideas about how we might do things differently generate hope. That’s a much-needed first step. These ideas contribute to putting major challenges and sparks of solutions related to the climate, energy, health and inclusivity on the map – consider the output of the What Design Can Do climate challenge, for example. But there’s so much more to be done. Does the average Dutch person even really understand what the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are all about?

When you look at what we’re doing as designers, it’s particularly striking that we’re not touching on the big themes which cut across all these societal problems. And one major problem lies with ourselves. We shout our good intentions from the rooftops, but when it comes to changing behaviour, we couldn’t care less. Why are we no longer focused on this? Of course, politicians’ crippling lack of vision and decisiveness is also a showstopper, but can’t we pick up the gauntlet ourselves?

It seems as if our thinking is still stuck in the classic silos of products, services and domains. And that the phenomenon of creativity is still too limited in its understanding and use. I’m extremely jealous of the anonymous ‘designer’ who came up with the idea of banning free plastic bags: it’s not about a product, it’s a systemic intervention. Since then, three-quarters of the Dutch population has been taking their own (plastic) bag to their local retailer without any com-plaints. It’s a shining example of influencing behavioural change with minimal intervention. Why are there still no Master’s programmes for behavioural change or design for politics?

As I’ve already mentioned, Dutch designers concerning themselves with societal issues has been a trend for quite some time. But besides contributing to awareness, have we really accomplished anything? Are we headed in the right direction? Making any progress? Or are we perhaps in over our heads? What role do we want to play, and if that role really is to make a difference, are we sufficiently equipped to do so?

Three years ago, in just about the northernmost tip of Scotland, I was delighted to happen upon a man collecting plastic in a ramshackle hut on Balnakeil Beach. Using a homemade Precious Plastic machine (designed by Dave Hakkens), he made key rings and other fairly trivial items. It was charming and hopeful, but also rather inconsequential. Which I so often see. I think the potential impact is far too slow.

Systems

If we zoom in on the major issues, without exception, they all relate to unmanageable systems. They are systems that we created ourselves, with many players and many (faulty) connections between them. Like our healthcare system. Isn’t it strange that all the data about your health is spread out over multiple parties, and yet it’s impossible to get all these details digitally in one place? Or our energy system, where you get barely anything in return for the energy you give back to the grid from your solar panels, despite the fact that you also made a long-term investment. How can we as designers exert more influence to shake up these systems – to make them more sustainable, more focused on broad social benefits, and good for the individual, the collective and the world?

We are too individualistic in it, and that is deeply ingrained in the DNA of the profession.

But back to Dutch Design Week for a minute. There you could also find individual designers who were engaged with social topics, but not ac-cording to a bigger plan. There’s nothing wrong with their intentions, however, strictly speaking, it seemed as if the solutions were flying in all directions, and were often rather noncommittal. At the same time, perhaps it’s also naïve to assume that as an individual designer you can change an entire system. We all far too self-absorbed, something that is deeply ingrained in the DNA of our profession. Just consider how our education is structured, how we talk about it and how we present ourselves. No other industry operates from the individual’s point of view as much as the design sector, and that no longer seems to fit with today’s ambitions and urgent concerns.

On the other hand, it can be argued that we work in a swarm, and that’s how we can make an impact. But a swarm of bees communicate continuously and operate as a whole; they have an instinct and a plan.

Disclaimer

And yet, there is also a disclaimer. I can remember a conversation I had in 2015 with the Director-General for Enterprise and Innovation at the Ministry of Economic Affairs as if it were yesterday. A few years back, the creative industries were named a ‘top sector’ as part of the government’s top sector policy. As a member of the Creative Industries Top Team, I regularly sat down with the ministry. The conversation that day started o! quite seriously. There were some imminent policy changes, and we as the creative industries, and certainly the designers, had to take that into account.

The original policy, which had been conceived in line with traditional business pillars, would slowly shift towards societal challenges such as climate change and the energy transition. So, if you as a sector wanted government money for research or foreign trade missions for example, you had to keep that in mind. The director general gave me a poignant look, leaned forward and softly said: ‘So you have to tell your designers they need to focus more on societal challenges.’ I fell silent for a moment.

In all honesty, he had a point. And he told the same story to the energy sector representatives and the Agri & Food top sector, of course. But it’s a whole different ballgame there, and you can’t really compare us and them. Those sectors are independent, they need to become more sustainable, and they can make a significant impact on society in and of themselves. They can independently affect change with generic measures (read: mostly painful decisions). But the situation is different in the creative sector, where design professionals make up the vast majority. We primarily work in the service of others and are paid by others, with a few exceptions. We are excellent at portraying change, but in most cases, cannot take ownership of it.

And that’s exactly what the conversation with the Director-General was about: the problem is that most societal issues don’t have an owner or a budget. Or, as Monocle so cleverly put it on the cover of their October issue: Who owns the weather? He agreed with my observation of course, but also expressed the hope that we would contribute as a sector, and should find a way to make it happen. More on that later.

It has long been the job of the government to take care of the public good. Which is why the administrators of the city of "ome installed sewers, and why Cornelis Lely, as Minister of Water Management, eventually managed to realize the Afsluitdijk (‘enclosure dam’ between North Holland and Friesland). Both were desirable and necessary interventions in the public interest with public ownership, based on a vision of a desired long-term e!ect.

Incidentally, the aforementioned political decisions often required making painful decisions – something which is also unavoidable with regard to the so-called ‘grand challenges’. I am convinced that this is an area where designers can help; we are masters at coming up with solutions that bridge conflicting interests. As far as I’m concerned, that goes beyond what activist designers can do, or questioning designers, or speculating designers. Those roles are relevant as well, but we can do so much more.

What is the role of designers?

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that the government will increasingly, or better yet once again, take responsibility for orchestrating and financing major changes. Then what can we do as designers? To start, we must embrace the complexity of these challenges more than ever before. That means we need to learn more about the ins and outs of these systems in general. We need to delve into the systems’ players as well as their relationships, their behaviour and how to bring about transformation. We also need to increase our expertise within our own discipline, and translate this expertise into design interventions. Along the way, there will be quite a few hurdles to overcome.

First of all, designers don’t like reading. And certainly not if they need to immerse themselves in systems theories, complexity models and how to influence them. Don’t get me wrong – I’m very excited about the progress we’re making in wanting to do good for the world. But if we really want to make a difference, we need to take firm steps and design in a more knowledge-driven way. It also means we need to embrace the lifelong learning principle that is now commonplace in other sectors. That’s outside of our comfort zone, but isn’t that what we’re also asking of others?

Anyone who studies systems theory knows that systems can be set in motion using interventions, and that you can experiment with them. As part of that, we can’t forget we are also operating in the context of a system, and it is essential to know the language of that system.

What can designers contribute?

Classic design thinking often refers to the power of imagination, creativity, taking an integrated approach to design issues and the ability to reframe them. These are extremely valuable skills that we must continue to cherish. After all, we can employ them in every domain and for a wide range of assignments. But will that give us the role that we so badly desire, or will we simply become another player within these transitions?

Over the past few years, the Creative Industries Top Team has been working to put KEMs (Key Enabling Methodologies) on the map and to better articulate them. These methodologies can be seen as the toolbox of creative professionals. For decades, creative professionals have used and developed methods, strategies, processes and tools to give structure and direction to their work. They establish ways of working (together), give guidance on how to describe problems and outline how to arrive at solutions. These tools assist with executing the work and creating an impact. They can be applied to a wide variety of domains.

It is precisely this shift in focus that will raise our profile among other sectors, where KEMs are now becoming more well-known. We have the tendency to put the things we design on display. But apparently, we are more likely to get a seat at the table based on how we find these solutions. That’s another insight that aligns with the wishes of the Director General of Economic Affairs. Looking back, we can see here the harbingers of things that were previously left unsaid. That’s how ‘scrum’ and ‘agile’ have become commonplace in many other sectors, for example – it’s because designers gave them the tools.

What's next?

If we want to take the next steps, four things are vital. First, let’s start by (1) embracing the complexity of the big challenges. It will also help if we (2) acquire and develop knowledge about how systems work. And please, let’s (3) operate as a collaborative, according to a bigger plan, from consortia. Our ability to excel with (4) our toolbox of strategies, methods and processes will also provide a considerable boost. Let’s learn to think bigger, because only then can we make a real contribution to the transformation process.

Finally, how to we get a seat at the table? The good news is that it’s already underway thanks to platforms like What Design Can Do and Dutch Design Week, which are increasingly inviting other industries to participate. And the opposite is also happening more and more. We’re just getting started. Design will never be the same...

Jeroen van Erp is partner and innovation strategist at Fabrique and Professor of Concept Design at TU Delft. Jeroen previously wrote this article as an essay for the Dutch Designers Yearbook 2021. A publication of the BNO, the Professional Association of Dutch Designers.

Dutch Designers Yearbook 2021

ISBN 978-94-6208-657-9

Available in Dutch, English